US President Donald Trump tours the Cameron LNG Export Facility May 14, 2019, in Hackberry, Louisiana. (Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images)

Inside the small agency with a grand plan for Trump’s global energy dominance

Briefing notes for the head of the U.S. Trade and Development Agency reveal how it’s working “in lock step” with the fossil fuel industry to push gas to emerging markets

April 23, 2025

With

Among the oil and gas executives and senior government officials from around the world at the major annual energy conference CERAWeek in Houston last month, one Donald Trump appointee cut an unassuming figure. He stayed at a modest $130/night hotel and was photographed in a gray open-collared shirt and a pair of well-worn tan shoes.

Little attention has been paid to Thomas Hardy’s appointment as acting director of the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, or USTDA. It is one of the smallest of the federal agencies and where he has spent the past two decades. But as the much bigger and better-known U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has been gutted, Hardy has quietly been overseeing a reorientation of foreign assistance in Trump’s vision for American energy dominance.

During the few days he spent in Texas, Hardy spoke at events alongside energy ministers from Turkey and Libya and met with major U.S. fossil fuel companies. He was invited to a cocktail reception hosted by the French oil giant TotalEnergies — the event would be “an opportunity to network with high level oil and gas industry representatives,” according to Hardy’s briefing book for the conference, which was obtained by the nonprofit investigative group the Centre for Climate Reporting and Rolling Stone.

As USAID projects designed to help poorer countries transition to cleaner forms of energy have been shuttered, a new brand of international assistance is emerging under Trump: one that benefits America’s economic interests as well. That’s no more apparent than at USTDA, which funds feasibility and planning studies for major infrastructure projects in emerging economies to spur U.S. jobs and exports. For the past four years, it has focused on clean energy. But now, Hardy’s briefing book shows, it is looking to work “in lock step with U.S. industry” to push natural gas around the world. According to the agency, it has already had “tremendous interest.”

The push could prove lucrative for the companies cashing in on America’s gas boom, which have helped the U.S. become the world’s biggest producer of fossil fuels and donated millions to reelect Trump. But critics worry that the president’s plans to make the U.S. the world’s gas station could come at a cost to both Americans and the climate. And for poorer countries who have limited funds for transitioning to cleaner forms of energy, committing to U.S. gas now means that the work of the Trump administration could be felt long after he has left the White House.

We have seen tremendous interest from our partners in emerging markets for support of their natural gas infrastructure

“Trump claimed an ‘energy emergency’ but now wants to send more of our energy overseas, which will raise prices for families here, at home,” said Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, the Rhode Island Democrat who is ranking member of the Senate Environment Committee. “The reverse Robin Hood scheme of making Americans pay to enrich fossil fuel billionaires is Trump’s modus operandi, and by shutting down more affordable, clean, domestic energy, he is putting us all on the fast track to climate and economic disaster.”

'Success stories'

Even before Trump took office, the U.S. fossil fuel industry was preparing for a huge expansion of its ability to ship gas overseas. Now, with the president vowing to unleash American energy, it has the full support of the government.

His Cabinet has extolled the virtues of the oil and gas that Trump has referred to as the “liquid gold under our feet,” as the administration has slashed environmental regulations and opened up federal lands for drilling. Trump has even suggested that countries could buy American-made liquefied natural gas, or LNG, as a way to close trade deficits and avoid steep tariffs.

Building on his campaign promise to “drill, baby, drill,” Trump and his Energy Secretary Chris Wright have begun granting new gas export authorizations, which were paused by Joe Biden early last year over fears of driving up prices for Americans and fuelling global warming. Wright, a fracking billionaire, has previously said that the country’s abundance of fossil energy could help alleviate poverty around the world while describing concerns about climate change as a “mania.”

Meanwhile, like many other parts of the U.S. government involved in foreign assistance, USTDA and its roughly 60 members of staff have been in limbo — its funds frozen and work under review. Over the past four years, its activity in the energy sector has focused on renewables and trying to clean up fossil fuels. In December, for instance, the agency announced a partnership with the Egyptian national oil company to help reduce emissions of the greenhouse gas methane. Other examples of initiatives supported by the agency under the Biden administration include a solar power project in Zambia and wind power in Indonesia.

But the agency’s work could look very different under Trump. On the day of his inauguration, USTDA published on its website five ‘success stories’ about its work: All five were related to fossil fuels, and all five related to projects it had funded during Trump’s first term. There have been no updates on the agency’s website or social channels since, other than a post on X and LinkedIn on February 3 announcing that “All USTDA activities are suspended until further notice.”

U.S. Trade and Development Agency Acting Director Thomas Hardy speaking at CERAWeek in Houston in March

But that didn’t stop Hardy, who also served as acting director for three years during Trump’s first term, from attending CERAWeek in March. He told Reuters on the sidelines of the conference that the agency was already shifting its focus: “Our approach is looking at all energy projects and not being hamstrung by only renewables as happened in the last four years,” he said. His briefing notes from the conference obtained via a FOIA request by CCR suggest that natural gas would be central to its efforts.

His draft answers for a CERAWeek panel on the African energy sector referenced Trump’s executive order on “unleashing American energy” signed on the first day of his second term.

“Areas of focus include options for reliable and affordable energy such as oil, natural gas, coal, hydropower, biofuels, critical minerals, and nuclear energy,” Hardy’s notes state. “Of these areas, USTDA anticipates the greatest concentration of its energy sector efforts may be in critical minerals, nuclear energy, and natural gas.”

As well as his public speaking commitments in Texas, Hardy met with major players in the U.S. gas industry, Cheniere and Excelerate Energy. A planned meeting with ExxonMobil did not go ahead, a spokesperson for the agency said. During the first Trump administration, all three companies participated in USTDA’s so-called ‘reverse trade missions,’ where the agency invites foreign governments and companies to meet with U.S. industry, according to Hardy’s briefing book.

He also met with GE Vernova, which works in the renewable energy sector but is a major supplier of turbines for gas-fired power plants. His briefing notes stated that he would “share details about USTDA’s planned programming in the energy sector under the Trump administration; and explore areas for collaboration.”

“We have seen tremendous interest from our partners in emerging markets for support of their natural gas infrastructure,” a USTDA spokesperson told CCR and Rolling Stone. “It is through projects like LNG import terminals and gas-fired power plants that these countries will be able to provide reliable and affordable electricity to their citizens. USTDA is working to make sure that U.S. companies are well positioned to win export deals when emerging markets invest in their energy infrastructure.”

The world simply can’t afford to increase our use of fossil fuels.

The briefing book also shows how the first Trump administration had previously sought to use USTDA to specifically boost gas. A memo included in the bundle, titled “Putting American Workers First while Ensuring U.S. Energy Dominance Globally,” mentioned nine USTDA-funded gas projects in countries across the world, including Sierra Leone, India and Vietnam, from Trump’s first term.

“During the Administration of President Donald J. Trump, USTDA prioritized an all-of-the-above energy strategy to open emerging markets for the export of U.S.-manufactured goods and services,” the memo stated. “Core to this focus was ensuring countries had the ability and capacity to import U.S.-produced LNG, making the United Sates [sic] an indispensable partner for energy production.” It added that “this commitment to energy development” led to over $1 billion in U.S. exports.

His notes state that the agency plans to “coordinate with the U.S. gas industry to launch an updated version of this initiative so that we can address their current and longer-term needs.”

Dr. Robert Howarth is a professor at Cornell University whose research informed the decision by the Biden administration to pause approvals of new LNG export licenses in January last year. He found that emissions may be much higher than previously expected.

“We need to be reducing our emissions from fossil fuels by half in the next 15 years or so if we’re going to avoid catastrophic runaway climate disruption. But here we are exporting LNG which has the largest footprint,” he said.

It would be “tragic” for the climate if countries such as Vietnam — where USTDA’s work during Trump’s first term helped “U.S. industry to supply technology for natural gas power plants,” according to Hardy’s briefing book — build out LNG infrastructure because of pressure from the U.S., he said. “The world simply can’t afford to increase our use of fossil fuels.”

A spokesperson for USTDA did not directly answer questions about the potential impact the agency’s work could have on the climate or whether it would continue to support renewable energy projects. The agency will “align its programming” with Trump’s Executive Order on Unleashing American Energy but it is still under review, she said. “Any resumption of program funding will fully align with the Administration’s foreign policy priorities for making America safer, stronger and more prosperous, including in the energy sector.”

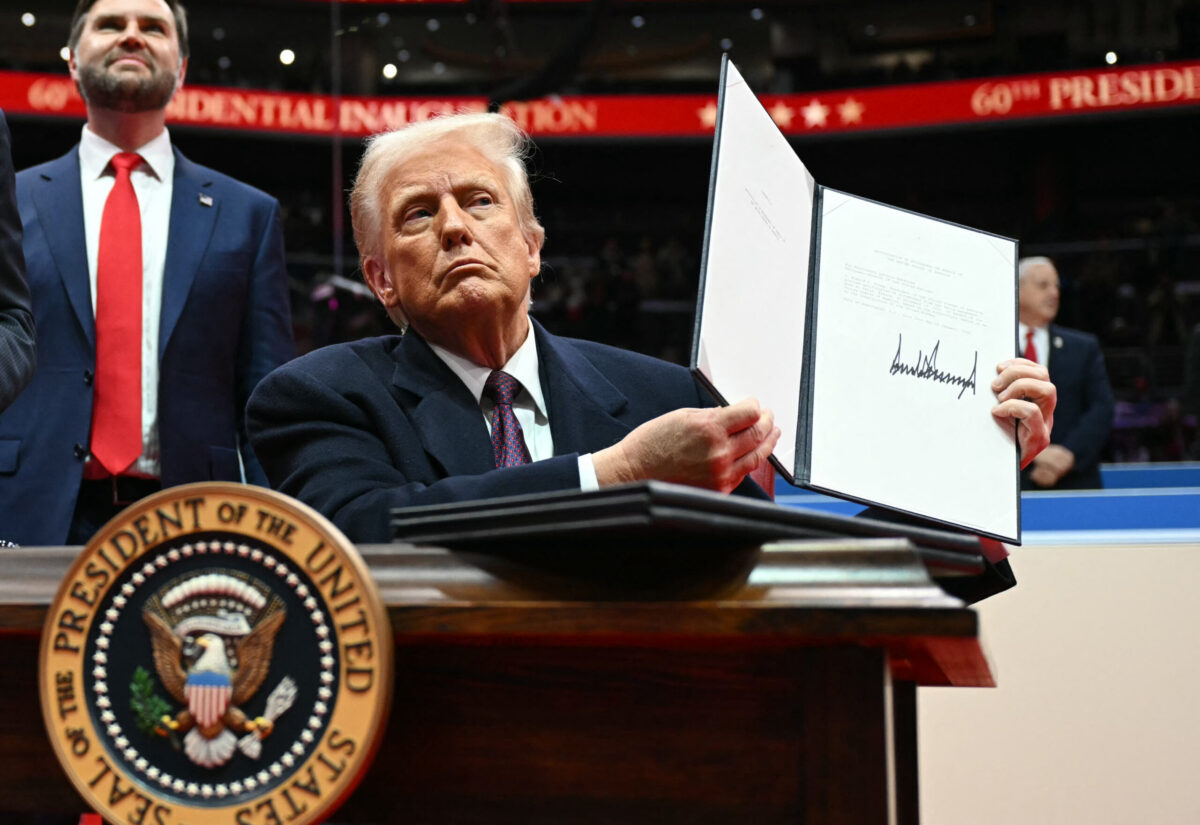

US President Donald Trump holds letter to the UN stating the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on January 20, 2025. (Photo by JIM WATSON/AFP via Getty Images)

'A transactional model'

The vision for a second Trump term as written last year by the coalition of conservative groups known as Project 2025 included calls to “scale back USAID’s global footprint” and “deradicalize” its programs. Of particular ire to the group was “the Biden Administration’s extreme climate policies” and “its anti-fossil fuel agenda.”

“The next conservative Administration should rescind all climate policies from its foreign aid programs,” it wrote in its Mandate for Leadership, the book published by the group.

Despite distancing himself from Project 2025 during the campaign, Trump’s gutting of USAID over recent months has largely followed this plan. More than 150 climate and clean energy contracts and grants managed by the agency have been terminated, according to an analysis by Politico’s E&E News.

The moves will have likely been cause for concern for those at USTDA. Project 2025 wrote that Congress should “eliminate” the agency, stating that its “activities more properly belong to the private sector.”

But a pivot to fossil fuels could show that USTDA is a valuable tool for an administration looking for a more transactional approach to international development. Its small team, which has staff in D.C. and in U.S. embassies across the world, can have a mighty impact: For every dollar it spends on programming, it generates on average $231 in U.S. exports.

A memo apparently being circulated by Trump aides suggests USTDA could be placed under the auspices of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), Politico reported last month. Rather than providing grants, DFC offers loans, makes investments, and provides insurance against political risks for private sector-led projects in lower and middle-income countries. The proposed plan is part of a broader retooling of overseas aid to “create a performance-based, transactional model.”

“This blueprint proposes a reimagined U.S. international assistance structure and set of operating principles that promises measurable returns to America while also projecting American soft power; enhancing our national security; and countering global competitors, including China,” the memo states. But there are questions about what the countries would get from U.S. aid focused on building out LNG import infrastructure and gas-fired power plants.

The industry has claimed that cheap, reliable LNG can be used as a transitional fuel for countries looking to move away from coal. But Sam Reynolds, a research lead at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said that for many countries, it does not make financial sense to import U.S. LNG, regardless of the consequences for the climate. He said that the cost of generating electricity from imported LNG is “orders of magnitude more expensive than renewables.”

In many cases, “there simply is no economic case to use LNG as a bridge fuel,” he said.

But he warned that pressure from the Trump administration on countries to buy U.S. gas could lead to “transactional LNG relationships rather than relationships based on sound economics. They’re based on security and fear and a need to assuage the current administration.”

Related